The Collections of the Spanish Kings

The Spanish

monarchs had a number of advantages over Charles I: they had been collecting

for eighty years before the young prince visited Madrid and viewed the glory of

their collections; they also had enjoyed the services of Titian as their

painter, and therefore had a large number of his works in their palaces. It was

to these gigantic holdings that the current King, Philip IV was to add old

masters from his regal “brother’s” collection, though he would acquire them

discreetly, not openly. Born in 1603, Philip had spent his childhood surrounded

by a dazzling array of the finest old masters ranging from Titian to great

Flemish artists like Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden. The wealth of the

Spanish collection owed much to the ambitions of the Hapsburgs, especially the

Emperor Charles V who considered art patronage an effective way of spreading

his political ideals. From 1532 Charles V had employed Titian and been rewarded

with such surpassing masterpieces as Charles

V with Hound, which was given to the future Charles I in 1623, but

subsequently rescued by Alonso de Cardenas.[1]

Titian would supply Charles V with pictures like the Gloria and Empress Isabella

from the 1530s until the Emperor’s abdication. Another dimension was added to

the Spanish collection with the acquisitions of Mary of Hungary, the Emperor’s

sister who governed the Netherlands from 1531 to 1556. Mary added Flemish

jewels to her collection like Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait and Rogier van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross, arguably the two finest Northern paintings

in the Spanish holdings. Not that she deserted Titian: she commissioned such

portraits as Charles V on Horseback

and the portrait of her nephew, Philip II of Spain (1555-98) who also was no

mean collector. The Spanish monarch who is remembered as the most

inconsequential was Philip III (1598-1621) who was responsible for losing

Correggio’s Leda and the Swan and the

Rape of Ganymede, which he sold to

his relative, Rudolph II.

The Collections of Rubens, Leganès and Haro

|

| Titian, Charles V Standing with His Dog, 1533, Oil on canvas, 192 x 111 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid. |

|

| Unknown Netherlandish Artist, Portrait of Mary of Hungary, c. 1550, Oil on panel, diameter 9 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. |

|

|

Rogier van der Weyden, Deposition, c.

1435, Oil on oak panel, 220 x 262 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

|

|

|

Jan van Eyck, Portrait of Giovanni

Arnolfini and his Wife, 1434, Oil on oak, 82 x 60 cm, National Gallery, London.

|

When Rubens

died in 1640, Spanish eyes turned on his collection which numbered several

hundred pictures, much antique sculpture, medals and cameos.[2]

From Rubens’s collection, Philip IV acquired about 29 paintings, including

copies after Titian that the Flemish painter had made in the Royal Palace. The

hoard included a number of Rubens’s own paintings like Nymphs and Satyrs, Titian’s Self-Portrait,

and Van Dyck’s Christ Crowned with Thorns

and the Arrest of Christ. A number of

subsidiary collections sprang up amongst a clan of connoisseurs including the

Marquis of Leganès who had spent time in Flanders studying the collections of

the Infanta Isabella, as well as smaller ones in Antwerp. There he met Rubens

who gave him the flattering title: “among the greatest admirers of this art

that there is in the world.” It is startling to learn that Leganès’s collection

consisted of 13 items in 1630, but by 1642 thanks to money, this increased to 1150,

1132 had been acquired in 12 years. As Brown says, Leganès exhibits the

“traditional Flemish-Italian bias of Spanish collectors.” So his collection

included 19 Rubens, 7 Van Dycks, and over a dozen animal paintings by Snyders.

Amongst the Italians, Leganès had some pretty spectacular names: Giovanni

Bellini, Palma il Vecchio, Giorgione, Perugino, Raphael, Leonardo, Veronese,

Bassano and Titian. Like the King, Leganès hardly owned any Spanish pictures! Another

member of this collectors’ clan was Luis de Haro, minister of Philip IV. Haro

was bankrolling Cárdenas during the English sales, but he also possessed an

excellent collection himself. Despite his status as a royal servant, He had his

own views on art. Though encouraged to buy “modern” art like Cigoli’s Ecce Homo, he rejected it because it

didn’t measure up to his Raphaels and Titians. One should also remember the

Duke of Lerma who owned a vast collection of paintings, including Veronese’s Venus and Mars, a picture later claimed

by the Prince of Wales. Rubens painted a magnificent equestrian portrait of

him.

|

| Paolo Veronese, Mars and Venus, 1570s, Oil on canvas, 165 x 126 cm, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh |

|

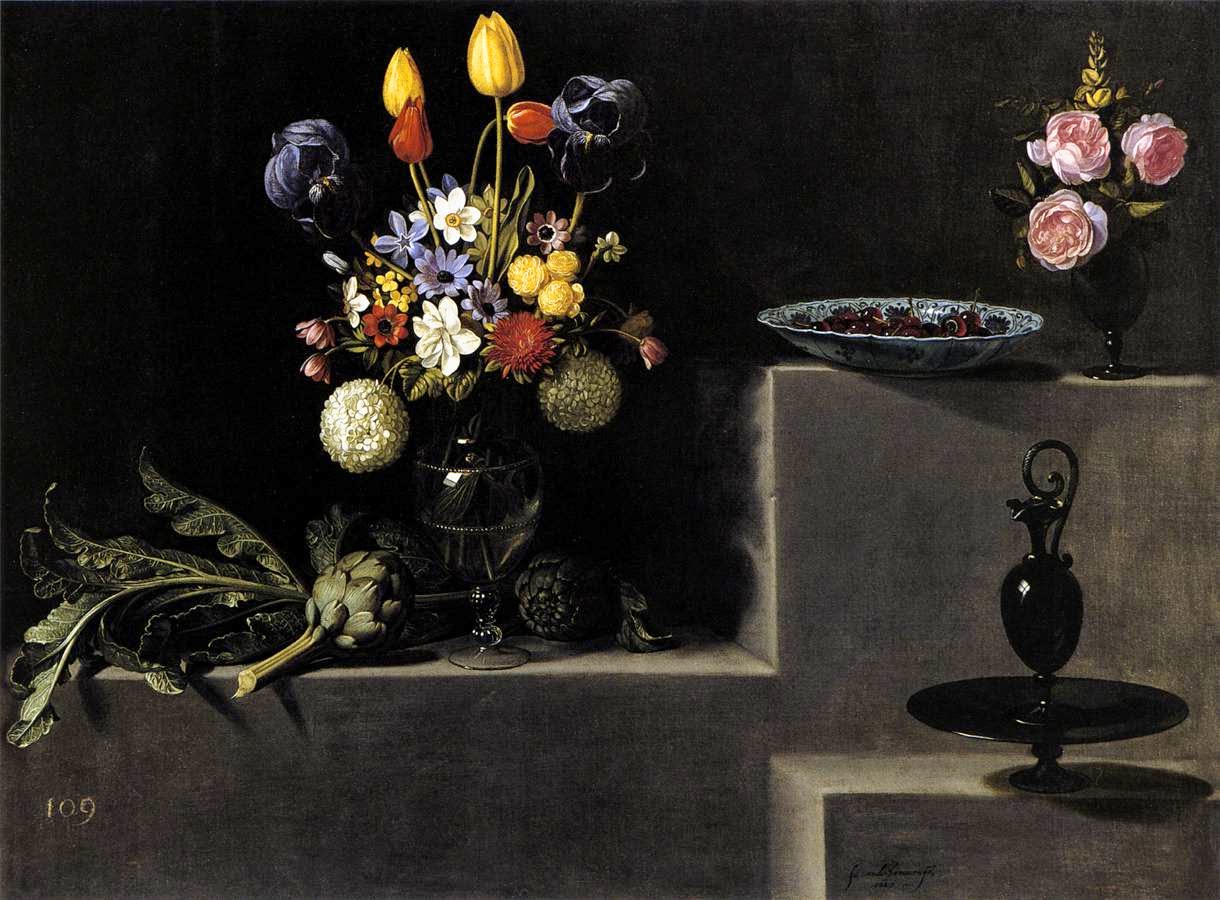

| Juan van der Hamen, Still Life with Flowers, Artichokes, Cherries and Glassware, 1627, Oil on canvas, 81.5 x 110.5 cm, Private collection. |

|

| Ludovico Cigoli, Ecce Homo, 1607, Oil on canvas, 175 x 135 cm, Galleria Palatina (Palazzo Pitti), Florence |

|

| Annibale Carracci, Venus, Adonis and Cupid, c. 1595, Oil on canvas, 212 x 268 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid |

Velasquez, the Royal Palaces and Collections

After Philip

IV had pushed French raiders out of Aragon, he put up his sword and spent more

time with his pictures. He also built a large hunting lodge, the Buen Retiro

which is known to have contained landscapes by an international cohort of

painters, including Poussin and Claude.[3]

Another smaller lodge, the Torre de la Parada may have housed mythological

works by Rubens and Jordaens.[4]

But the most important palace was the Alcazar of Madrid where Philip worked

with his curator Velasquez to plan the organization of his galleries and the

decoration of the palace.[5]

In the Alcazar inventory of 1686, the breakdown was as follows: Titian (77),

Rubens (62), Tintoretto (43), Velasquez (43), Veronese (29), Bassanos (26). In

El Escorial, there were 19 more canvases by Titian, 11 more by Veronese, 8 by

Tintoretto and 5 by Raphael. A cautious estimate might be by 1700, the 12 royal

seats housed no fewer than 5,539 paintings compared to roughly 1500 at the

death of Philip II. [6] As

Brown says, adding a thousand acquired during the reigns of Philip III and

Charles II, that would be around 3,000 acquired directly/indirectly by Philip

IV. As the French cleric, Jean Muret wrote on a visit to Madrid in 1667: “I can

assure you, Sir, that there were more [pictures in the Buen Retiro] than in all

Paris. I was not at all surprised when they told me that the principal quality

of the dead king was his love of painting and that no one in the world

understood more about it than he.” Given these incredible numbers, Philip IV as

art collector ranks well above Charles I.

|

| Claude Lorrain, Landscape with Mary Magdalene, oil on canvas, 162 x 241 cm, Prado, Madrid. |

|

| Nicolas Poussin, Landscape with St Jerome, c. 1637-8, oil on canvas, 155 x 234 cm, Prado, Madrid. |

|

| Diego Velasquez, Philip IV, 1624-27, Oil on canvas, 210 x 102 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid. |

|

|

Diego

Velasquez, Self-Portrait, c. 1640, Oil on canvas, 46 x 38 cm, Museo de

Bellas Artes, Valencia.

|

Velasquez and Titian.

In the year

that Charles I and the English connoisseurs were attending the famous seminar

in Madrid, 1623, Velasquez was appointed painter to Philip IV. By the time he

painted the Philip IV Standing, he

had had several years to familiarize himself with the royal collection. In

1660, the Italian critic Boschini said of Velasquez: “He loved the Painters

very much, Titian most of all, and Tintoretto.”[7]

In the 1670s, Jusepe Martinez said that Velasquez had a connoisseur’s knowledge

of Titian’s art when he said that paintings of Titian done by Sanchez Coello

had passed for originals, which Velasquez admitted. As stated above, the Hapsburgs

collected Titian’s art with voracity and obsession; but they also acquired

paintings by Veronese, Tintoretto and Bassano, all of whom displayed techniques

derived from close study of Titian. In the fateful year of Charles I’s

execution, 1649, Velasquez would have been on a buying expedition for the King

in Rome; he may have returned to Venice in 1651 and obtained pictures there too

including examples of Venetian art.[8] His debt to Titian is visible in the

backcloth of Las Hilanderas which has

a direct quotation from the Venetian master’s Rape of Europa which came into the collection during the reign of

Philip II. Rubens is known to have copied this and in Velasquez’s eternal

masterpiece, Las Meninas, there may be reminiscences of it in the

paintings in the background.

|

| Diego Velasquez, The Fable of Arachne (Las Hilanderas), c. 1657, Oil on canvas, 220 x 289 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid. |

|

|

Diego Velasquez, Las Meninas or The

Family of Philip IV, 1656-57, Oil on canvas, 318 x 276 cm, Museo del Prado,

Madrid.

|

|

| Titian, The Rape of Europa, 1559-62, Oil on canvas, 185 x 205 cm, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston |

Slides.

1) Titian, Charles V Standing with His Dog, 1533, Oil on canvas, 192 x 111 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

2) Titian, Portrait of Isabella of Portugal (1503-39), 1548, Oil on canvas, 117 x 93 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.[9]

3) Titian, The Trinity in Glory, c. 1552-54, Oil on canvas, 346 x 240 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.[10]

4) Unknown Netherlandish Artist, Portrait of Mary of Hungary, c. 1550, Oil on panel, diameter 9 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

5) Rogier van der Weyden, Deposition, c. 1435, Oil on oak panel, 220 x 262 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

6) Jan van Eyck, Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and his Wife, 1434, Oil on oak, 82 x 60 cm, National Gallery, London.

7) Robert Campin, The Marriage of Mary, c. 1428, Oil on panel, 77 x 88 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

8) Joachim Patinir, Temptation of St Anthony, c. 1515, Oil on panel, 155 x 173 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

9) Hieronymous Bosch, Triptych of Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1500, Oil on panel, central panel: 220 x 195 cm, wings: 220 x 97 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

10) Hieronymous Bosch, (left wing Paradise,), c. 1500, Oil on panel, 220 x 97 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

11) Titian, Emperor Charles V at Mühlberg, 1548, Oil on canvas, 332 x 279 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.[11]

12) Titian, Portrait of Philip II (1527- 1598) in Armour, 1550-51, Oil on canvas, 193 x 111 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.[12]

13) Correggio, Leda with the Swan, 1531-32, Oil on canvas, 152 x 191 cm, Staatliche Museen, Berlin.[13]

14) Correggio, The Rape of Ganymede, 1531-32, Oil on canvas, 163.5 x 70,5 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum.[14]

15) Ludovico Cigoli, Ecce Homo, 1607, Oil on canvas, 175 x 135 cm, Galleria Palatina (Palazzo Pitti), Florence.[15]

16) Guercino, Susanna and the Elders, 1617, Oil on canvas, 175 x 207 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

17) Guido Reni, Atalanta and Hippomenes, c. 1612, Oil on canvas, 206 x 297 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.[16]

18) Annibale Carracci, Venus, Adonis and Cupid, c. 1595, Oil on canvas, 212 x 268 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.[17]

19) Peter Paul Rubens, Equestrian Portrait of the Duke of Lerma, oil on canvas, 283 x 200 cm, Prado, Madrid.

20) Paolo Veronese, Mars and Venus, 1570s, Oil on canvas, 165 x 126 cm, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh.[18]

21) Jusepe Leonardo, The Marquis of Leganés (on horse on the right) at the Surrender of Jülich, oil on canvas, Prado, Madrid.

22) Peter Paul Rubens, Annunciation, c. 1628, Oil on canvas, Rubens House, Antwerp.

23) Juan van der Hamen, Still Life with Flowers, Artichokes, Cherries and Glassware, 1627, Oil on canvas, 81.5 x 110.5 cm, Private collection.

24) Raphael, Madonna with the Fish, 1512-14, Oil on canvas transferred from wood, 215 x 158 cm, Museo del Prado.

25) Diego Velasquez, Self-Portrait, c. 1640, Oil on canvas, 46 x 38 cm, Museo de Bellas Artes, Valencia.

26) Diego Velasquez, Philip IV, 1624-27, Oil on canvas, 210 x 102 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

27) Claude Lorrain, Landscape with Mary Magdalene, oil on canvas, 162 x 241 cm, Prado, Madrid.

28) Nicolas Poussin, Landscape with St Jerome, c. 1637-8, oil on canvas, 155 x 234 cm, Prado, Madrid.[19]

29) Peter Paul Rubens, Judgment of Paris, Prado, 1638-9, oil on canvas, 199 x 379 cmMadrid, Prado.[20]

30) Diego Velasquez, Venus at her Mirror (The Rokeby Venus), 1649-51, Oil on canvas, 122,5 x 177 cm, National Gallery, London.[21]

31) Diego Velasquez, The Fable of Arachne (Las Hilanderas), c. 1657, Oil on canvas, 220 x 289 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

32) Titian, The Rape of Europa, 1559-62, Oil on canvas, 185 x 205 cm, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.[22]

33) Diego Velasquez, Las Meninas or The Family of Philip IV, 1656-57, Oil on canvas, 318 x 276 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

34) Diego Velasquez, Portrait of Philip IV, 1652-53, Oil on canvas, 47 x 37,5 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

[1]

Given to Prince Charles along with A Girl

with a Fur Wrap and the Pardo Venus.

[2]

Jeffrey Muller, Rubens as Collector, (Princeton, 1989).

[3] The

Spanish ambassador in Rome, Manuel de Moura commissioned around 50 landscapes

from leading artists who specialised in it. Claude and Poussin participated,

though not Salvator Rosa. For Poussin’s group of pictures, see Blunt, “Poussin

Studies VIII: A Series of Anchorite Subjects Commissioned from Philip IV”, Burlington

Magazine, Vol. 101, No. 680, (Nov 1959), 387-390. In 1634 Velasquez sold 18 paintings to the

Crown including two of his works painted in Italy. By 1634 the Buen Retiro

contained at least 800 pictures (Brown, Kings,

122).

[4]

Paintings in the Torre de la Parada numbered about 175, over 60 of which were

mythologies by Rubens and his workshop (now in the Prado) and another 60 of

animal and hunting scenes by Snyders and other animal painters.

[5] By

1640, the Royal Collection was about a 1000 pictures greater than it had been

10 years earlier. (Brown, Kings,

123).

[6]

All in Brown, Kings, 145.

[7]

Cited in Gridley McKim Smith, Greta Andersen- Bergdoll, Richard Newman, Examining

Velasquez, (Yale, 1988), 34. This section is indebted to the technical discussion

of Velasquez and Titian.

[8]

Velasquez first visited Italy in 1629; he landed at Genoa, visited Milan, and

then journeyed to Venice. From Venice he went to Rome and Naples, and from

there back to Madrid, arriving early in 1631. After 20 years, he returned to

Venice in 1649, arriving on May 21st.

[9]

Married Charles V in 1526 but died very young when only 36. This is a

posthumous portrait.

[10]

In a codicil to Charles V’s will, the Emperor described this painting; he also

ordered that a high altar should be constructed containing this painting.

[11]

This painting was commissioned to commemorate the Emperor’s victory over the

Protestant forces at the Battle of Mühlberg on 24th April 1547. The

red is supposed to indicate the colour of the Catholic faction in the religious

wars of the 16th and 17th centuries.

[12]

Philip was the only son of Charles V and Isabella of Portugal. In 1551 he

became Regent of Spain, and after his father’s abdication, King of Spain.

[13] Acquired

along with Ganymede; these 2 pictures probably part of a series of the “Loves

of Jupiter” (Danae, Berlin; Io, Vienna). L’opera completa del

Correggio, No. 78.

[14] L’opera

completa del Correggio, No. 80.

[15]

Offered to Haro, but rejected by him. “And even if this picture happened to be

among Cigoli’s finest, it could scarcely win a place in Don Luigi’s gallery,

where are so many excellent ones by artists of the first class, including

Titian, Correggio, Raphael, Andrea del Sarto and others.” Cited in Brown, Kings and Connoisseurs, 157. Cigoli’s

stock has risen since the 17th century. Four of his pictures

(including the Ecce Homo) were shown

in The Genius of Rome exhibition

(London, 2000), No. 99.

[16] Bought

by Philip IV from Giovanni Francesco, Marquis of Serra in 1664. Listed in the

inventory of the North gallery (Alcazar) made in 1666: “ A painting measuring

three varas in length and two in height, by the hand of the Bolognese, of the

fable of Atalanta, with a [Canceled: gilded] black frame, [appraised] at two

hundred fifty silver ducats.” One wonders if the palm leaf was a concession to

Spanish prudery which seems a more viable reason than Spear’s “psycho-sexual”

explanation in Richard E. Spear: The “Divine” Guido: Religion, Sex, Money

and Art in the World of Guido Reni, (Yale, 1997, 65.) This 1666 inventory

of the North Gallery in the Alcazar is reproduced in Orso’s Velasquez, Los

Borrachos, Appendix D.

[17] Bought

from the Marquis of Serra in 1664 and recorded in the inventory of the Alcazar two

years later. There is a version in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna which

is likely to be a copy, not least because of the truncation of the dog’s head.

For an illuminating discussion of this, see Michael Daley of Artwatch’s

comments- link and the comments in L’opera completa di Annibale Carracci,

(Milan, 1976), No. 44a.

[18]

Acquired by Philip III in 1606; inherited by Philip IV in 1621; given to

Charles I in 1623; commonwealth sale, 1649-50 etch. See The Age of Titian for full provenance.

Edinburgh, 2004, No. 69. And included in the recent Veronese exhibition.

[19] First

recorded in the Spanish collection in 1700. Rejected by Grautoff (follower of

Salvator Rosa). Blunt himself initially ascribed it to the “Silver Birch

Master”. In the article cited above and his CR, he said that he changed his

mind when he “saw the picture in a good light.” See Blunt, The Paintings of

Nicolas Poussin, 1966, No. 103. Generally accepted, and it may help to

resolve the “problem” of the Silver Birch Master since the trees in paintings

assigned to that individual are similar to the ones in this. Conclusion?

Poussin is the Silver Birch Master! Christopher Wright, Poussin Paintings: A

Catalogue Raisonné (Jupiter Books, 1984), No. 145.

[20]

Damisch said that it had been painted for the Torre de la Parada hunting

pavilion where another mythology (Jordaen’s Wedding

of Peleus and Thetis) hung. Hubert Damisch, The Judgment of Paris

(University of Chicago Press), 275. As Damisch also notes (176), the Infante

Ferdinand, Governor of the Low Countries, “was most astute when he informed his

brother Philip IV that Rubens had finally completed the canvas and that all the

painters agreed it was his finest work…he offered his own opinion..” The three

goddesses are too nude.””

[21] Purchased

by the NACF in 1906. For the provenance of this famous masterpiece, see Lynda

Nead’s essay in Saved! 100 Years of the National Art Collections Fund,

Richard Verdi and co, (2004), 74-79.

[22]

Rubens painted copies after Titian when he visited Madrid in the 1620s. He may

have done his copy of the Rape of Europa

in front of the King. “I know him (Philip IV) by personal contact, for since I

have rooms in the palace, he comes to see me almost every day.” Brown, Kings,

117.